|

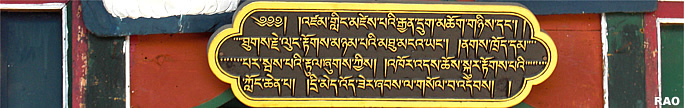

Dzongkha:

Bhutan's National Language

|

|

Bhutan's

Culture: Dzongkha |

|

Bhutan Information |

|

|

|

|

Dzongkha

: Origin and Description

|

|

The

modern Dzongkha writing uses the alphabet system first introduced by Thonmi

Sambhota. Son of Anu of the Thonmi clan from central Tibet, Sambhota

was the most intelligent minister of the religious Tibetan king Songtsen

Gampo (Srong-btsan-sgam-po). He was believed to be an emanation of

Manjushiri, the Lord of wisdom. The king sent Sambhota with fifteen other

young Tibetans to study Sanskrit in India. Sambhota studied linguistics

at the feet of Pandita Devavidhayasinha and Brahmin Lipikara of Kashmir.

Since he was the brightest student, his teachers called him "Sam-bhota"

meaning "best Tibetan".

After

mastering linguistics in India, Sambhota went back to Tibet and introduced

the Tibetan alphabet system along with king Songtsen Gampo which comprises

of thirty consonants and four vowels. The sound system and the structure

of the alphabet were based on Devanagari, a script used for many modern

and older languages of India, including Sanskrit, Hindi, and Nepali. Although

the writing system (namely Jogyig) was brought to Bhutan by Dematsema

(ldanma-Tsemang) on the invitation of Sindhu Raja, the origin of the

Bhutanese alphabet has to be traced back to Sambhota since the jogyig

is also based on his alphabet. Initially, Sambhota wrote eight aspects

of Tibetan grammar but only two - Sumchupa (sum-bcu-pa) and Takijugpa

(stags-kyi-yjug-pa) are extant today.

For

this reason, Dzongkha grammar is one of the easiest as opposed to the universal

claim that it is too complicated and hard to comprehend. Other languages

have all these aspects of grammar or more but Dzongkha is condensed into

these two, making it comparatively easy to understand and remember.

The

thirty consonants of Dzongkha alphabet, traditionally called selje sumchu

(gsal-byed-sum-bcu), are classified into seven groups of four and one

group of two (the last two letters ha and ah) according to yigui kye

ne (yigei-skye-gnas) "place of articulation". Most of these sounds

are produced by a pulmonic egressive airstream mechanism, i.e., sounds

are mostly produced by pushing out air from the lungs.

Most

of the manners of articulation are carried out by the tongue with other

organs such as labial (lips), dental (teeth), hard and soft

palate, velum, glottis, and so on. Because of the lack of such biological

terms for most of the body parts in Tibetan, all the consonant groups are

named with the initial letter of the group such as Ka-de (ka-sde) "Ka-group" for the first four letters ka, kha, ga, and nga, Ca-de (ca-sde)

"Ca-group" for the second four letters ca, cha, ja, nya, and

so on. For manners of articulation, activities are carried out by means

of nangdu threpa (nang-du-phradpa) "internal touching", cungze

threpa (cung-zad-phradpa) "slight touching", tsumpa (btsum-pa) "closing",

and chewa (phye-ba) "opening". These traditional linguistic terms

indicate that the lack of labels did not prevent Sambhota from identifying

the mechanism and manner of articulating these consonants and vowels.x

|

Modern

linguistics analysis show that there are reasons why Sambhota kept ka,

kha, ga, and nga in one group, ca, cha, ja, and nya in another group, ta,

tha, da, and na in yet another group, and so on till ha and ah.

This is because the first four letters - ka, kha, ga, and nga are called

velars. They are produced by raising the back of the tongue to the

soft palate or velum.

The

second four letters - ca, cha, ja, and nya are called palatals because

they are produced by raising the front part of the tongue to a point on

the hard palate just behind the alveolar ridge.

Ta,

tha, da, and na are called interdentals (between the teeth) as they

are produced by inserting the tip of tongue between the upper and the lower

teeth.

Pa,

pha, ba, and ma are called bilabials since these sounds are articulated

by bringing both lips together.

Likewise, tsa,

tsha, zra, wa, zha, za, oa, ya, are called fricatives and affricates

depending on where and how they are articulated. Ra and la together

are called liquid sounds. Specifically, ra is called rhotic and

la is called lateral. In producing ra sound, the tongue tip is raised

to just behind the alveolar ridge and therefore it is also called alveolar

glide. In the production of lateral sound la, the front part of the tongue

makes contact with the alveolar ridge, but the sides of the tongue are

down, permitting the air to escape laterally over the sides of the tongue.

Sha

and sa are called fricatives. In the production of these sounds, the

airstream is not completely stopped but is obstructed from flowing freely.

When you utter these two sounds, you will feel the air coming out of your

mouth. The passage in the mouth through which this air passes is narrow

causing friction or turbulence.

The

last two letters - ha and ah are called glottals. In producing these

two sounds, the glottis is open and no other modification of airstream

mechanism occur in the mouth. The air is stopped completely at the glottis

by closed vocal cords.

So,

we see that Sambhota has arranged the thirty consonants into groups in

order of their place and manner of articulation.

The

consonants are also classified according to their manners of articulation

such as ug chewa (dhugs-che-ba) "voiced", ug chungwa (dhugs-chung-ba)

"voiceless", drathoen chewa (sgra-thon-che-ba) "hard sounds",

and drathoen chunwa (sgra-thon-chung-ba) "soft sounds". Analysing

phonetically, such letters as pa, ta, ka, and sa in Dzongkha are voiceless

sounds (dbugs-chung-ba).

In

producing these sounds, the vocal cords are apart when the airstream is

pushed from the lungs. The air is not obstructed at the glottis, and it

passes freely into the supraglottal cavities. Because of this, they are

called voiceless sounds.

On

the other hand, such letters as ba, da, ga, and zra in Dzongkha are

voiced sounds (dbugs-che-ba) because when these sounds are produced,

the vocal cords are together and the airstream forces its way through and

causes them to vibrate. Hence, they are called voiced sounds.

Contributed

by Pema Wangdi,

Australian

national university

| Information on Bhutan |

|

| Links |

|

|

|

External

Links |

|